This morning, as I was hard at work in my study, I had occasion to take down the stout and handsome volume of Christian Dogmatics by J.J. Van Oosterzee, second edition, 1878. For the first time I saw the signature on the title page, 'R.F. Horton, Sept 1881, Dunedin, Hampstead'.

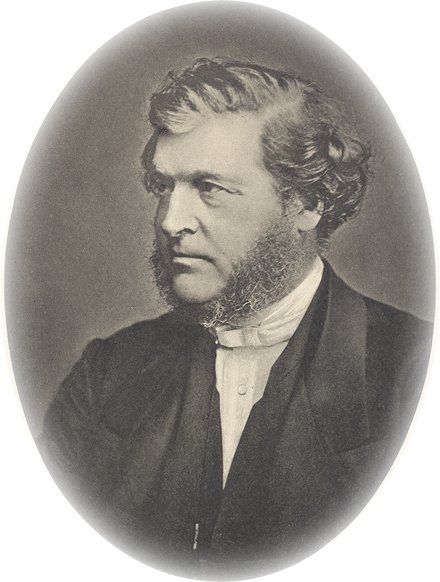

This morning, as I was hard at work in my study, I had occasion to take down the stout and handsome volume of Christian Dogmatics by J.J. Van Oosterzee, second edition, 1878. For the first time I saw the signature on the title page, 'R.F. Horton, Sept 1881, Dunedin, Hampstead'.The eyes rested on the words, and I thought 'have I read them correctly? Is this really a volume from the library of the famous preacher of the early 20th century, Robert Forman Horton (see cartoon)?' The answer, after a little research, was yes, it is. His signature in 1881 is a little different from that of 1910 that appears in his autobiography, but it is the same hand. 'Dunedin' was his address at the time. I had a book from a noted man's library, complete with his underlinings to highlight passages he liked!

And that set me thinking about books in general. We own books; we ministers have many books, they are our helps in study, and good books are like old friends. Some books we allow to pass through our hands pristine and untouched, others get used. The marks of a previous owner can be seen as annoying when it is a fellow-unknown, a man who lived in the same relative obscurity we do, but when it is a man like Horton, a known, then suddenly those markings are important! Double standard, I thought, why shouldn't the markings by William L. Holder in his copy of Westcott's The Gospel According to St. John be just as valued? Or the many and varied marginal notes made by Wesleyan theological students at Richmond in the margins of the College's copy of Calvin's Commentaries on Genesis? Sheer prejudice, surely!

This is part of the joy of second-hand books; we are not their first owners, we are their stewards who hand them on to the next generation. They had owners before us, and unless the Lord comes again, or they shall be consumed in a catastrophe, they shall have owners after us. They come to us from all directions, some from great public libraries like Liverpool and Norwich, others from the libraries of theological colleges in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, The United States and Canada, great and small college libraries give up their stock. Yet others come from Church libraries, as the old is removed to make way for the new. But the vast majority come from private libraries, great and small. Bought and sold, the books move around, making one combination, then another. Books that belonged to men poles apart theologically come together in the library of a third man; books from Monasteries are found side-by-side with volumes from Free Church ministers. Books sent to Canada return from there to the shores from which they departed a century and more before, while other books remain within the narrow geographical limits within which they were sold.

Some books have spent all their working lives (as it were) in large libraries, and seem somehow lost in the smaller compass of a minister's study. Others bear in their bindings the marks of their previous exalted position, and seem to have come down in the world in their transition to the study, while others are in bindings so humble they look embarrassed to be found in such exalted company as Mr. Horton's copy of Van Oosterzee, which has a binding to match its background.

And by those books we hold fellowship, not only with the men who wrote them, but also in some ways with the men who read them before us. Those signatures in the front, those underlinings in the text, they all say that others have been there before us, and those others may still, by their marks and annotations, be there still to guide us, to argue with us, to held us and to annoy us. And that is the Communion of Old Books.

1 comment:

Nice comments, and I find myself in entire agreement.

Post a Comment