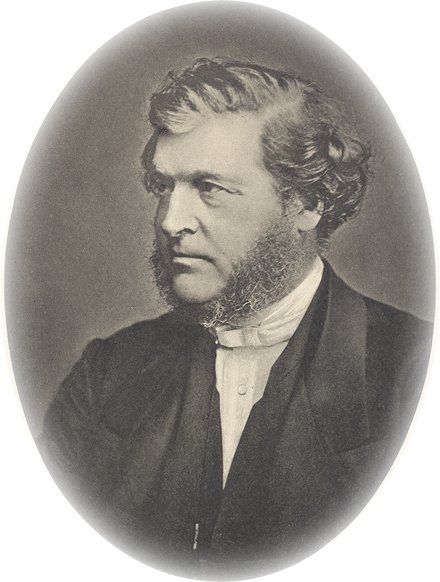

The Church of St. John, on the Buxton Road in Ashbourne, is a very different building from St. Mary, Mappleton, and yet the two are in some ways very similar. Most notably, they are Anglican buildings that are intended to be "Protestant", auditory spaces for the preaching of sermons rather than "Catholic" spaces for the drama of the Mass. While Mappleton was a new Church on an old site, built because of the decay of the old building, St. John's was built as the result of a disagreement in the Parish Church of All Saints in the 1860s. The Vicar, it would seem, was influenced by the ideas on theology and worship coming from Oxford and Cambridge, while one of the the leading local industrialists, Francis Wright, led a Protestant party. Eventually Wright and his friends left the Parish Church, but not the Church of England. They built a grand propriety chapel - a private church not connected to the Parish system - and paid for a minister for themselves

The chapel was of course St. John's. There is nothing terribly unusual in a wealthy man of the period building his own Church - it was done by people of all shades of Anglican theology, and there are also Nonconformist and Roman Catholic places of worship that deserve the title. These buildings, being largely the result of one man's piety, are sometimes very personal in their architecture, and can be theological statements in stone or brick. One example of the theology of St. John's architecture is the tymapnum over the west door, which is also the main entrance. It bears the words of Jesus from Matthew 18:20, "Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them." This is the Protestant (and even Nonconformist!) idea of the "gathered Church" rather than the Parish model, the Church as the company of God's elect, the "little flock" in the midst of the world

There is however nothing little about St. John's. This is Protestantism on the grand scale, a great auditory space like Spurgeon's Tabernacle in London, taking advantage of modern technology - and not coincidentally Francis Wright's own ironworks - to create a huge open worship area. Narrow columns of cast iron create the minimum interruption, and if the communion table is (as in our picture) occasionally obscured, the pulpit is not.

There is however nothing little about St. John's. This is Protestantism on the grand scale, a great auditory space like Spurgeon's Tabernacle in London, taking advantage of modern technology - and not coincidentally Francis Wright's own ironworks - to create a huge open worship area. Narrow columns of cast iron create the minimum interruption, and if the communion table is (as in our picture) occasionally obscured, the pulpit is not.

This is deliberate: The pulpit is the most important item in St. John's, where the Gospel is to be preached from. It would have originally also had a reading-desk beside it from which the service would have been read. By the 1870s the age of the three-decker pulpit was well and truly past, but still the simple woodwork of the pulpit looks back to an earlier age. Though the form of the building is Romanesque externally, even to the apse (which provides a conveniently shallow chancel), the interior is pure Victorian Protestantism.

Looking west, the effect is even more pronounced. It could be a Nonconformist chapel, and the vicar at All Saints' who provoked the secession would no doubt have pronounced it as good as one. A Nonconformist chapel would, of course, have provided a deeper gallery than the one at St. John's, which seems to have been intended for singers and musicians, but that is all. The singing gallery was also a Protestant statement - the Anglo-Catholics had their robed choirs in stalls in the chancel or Choir of the Church.The pews of St. John's are said to seat over 600. Tall windows with clear glass flood the wide preaching-Church with light in contrast to the "dim religious light" filtered through stained glass.

Cast-iron windows are another reminder that the man who paid for this was the owner of an ironworks. The style of tracery is one to be found in many Nonconformist places of worship - not coincidentally including Ashbourne's Wesleyan chapel! This is Victorian Anglican Protestant militancy in stone and iron - and a wonderful building it is too.

No comments:

Post a Comment