Michael Haykin has written an excellent post over at the Andrew Fuller Centre on the subject of criticizing Andrew Fuller. A quotation used by Dr. Haykin in the post struck us as particularly apt:

“Once for all, we must enter our protest against that system of wholesale condemnation, that will admit of nothing good in a man, if some part of his divinity system happen to be open to question.”This is excellent advice, especially as it comes from a critic of Fuller. We have begun serious study of John Calvin in preparation for a lecture that we shall be giving in Surrey, God willing, some time next year, and if ever there was a man concerning whom the wise words of this old book review whom Haykin quotes were often broken, it is the Reformer of Geneva. From Jerome Bolsec through every sort of silly Arminian and Romanist, to Dave Hunt and Nelson Price (from the ridiculous to.. the ridiculous), Calvin has been besieged by all sorts of men who have decided that, because they do not agree with Calvin's theology, he must have been the greatest monster who ever lived.

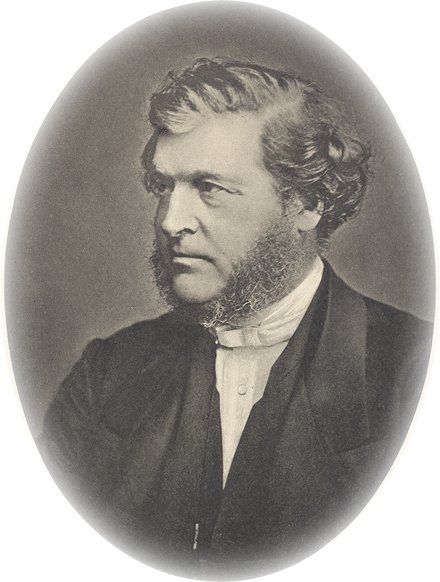

It was therefore refreshing to receive by post this morning Volume 2 of the Cambridge Modern History (first published in 1903), which contains a delightful essay on Calvin and the Reformed Church by Principal A.M. Fairbairn of Mansfield College, Oxford (pictured). A lifelong Arminian and forthright critic of Calvin's theology (let it never be said we only read biographies of Calvin by Calvinists!), Fairbairn nevertheless refused to ignore the good that Calvin had done. Of Fairbairn's essay, his biographer, W.B. Selbie, writes:

"In Calvin Fairbairn had a subject altogether to his mind, and his study of him is among the best things he ever wrote. He always distinguished between the man and his system. Of the latter he had been a convinced and determined critic from the earliest days of his ministry. But he always recognised the great part it had played in the development of Christendom, and he would never suffer the good that was in it to be forgotten. For the man he had a genuine admiration. In describing him as one whose mind was the mind of Erasmus, while his faith and conscience were those of Luther, he struck a point of affinity with himself that could not fail to win his sympathy." (The Life of Andrew Martin Fairbairn [Hodder and Stoughton, 1914] Pp. 403-4)Like Arminius himself, he lauded Calvin's work as a commentator to the skies. Indeed, We doubt that any Calvinist has been so immoderate in praise of Calvin:

"His services to the cause of sacred learning must not be forgotten. These it is hardly possible to exaggerate; he is the sanest of commentators, the most skilled of exegetes, the most reasonable of critics. He knows how to use an age to interpret a man, a man to interpret an age. His exegesis is never forced or fantastic; he is less rash and subjective in his judgments than Luther; more reverent to Scripture, more faithful to history, more modern in spirit. His work on the Psalms has much to make our most advanced scholars ashamed of the small progress we have made either in method or in conclusions. And his work is inspired by a noble belief; he thought that the one way to realise Christianity was by knowing the mind of Christ; that this mind was to be found in the Scriptures; and that to make them living and credible was to make indefinitely more possible its incorporation in the thoughts and Institutions of man." (Cambridge Modern history, Vol. 2 P. 376)And what Calvinist can disagree with this Arminian? It warmed our heart to know that Calvin's personality and skill as a commentator had won the sincere admiration and regard of the Oxford scholar.

No comments:

Post a Comment