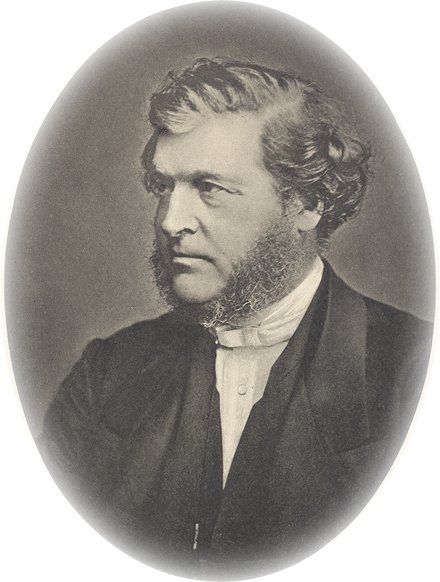

The latter part of the 19th century was an age of great preachers. The names of Spurgeon, Maclaren, Parker and Dale are chief among the greats of the English pulpit in that era. R.W. Dale of Birmingham was one of the greats of the Congregationalists. He is best known for his able defence of the atonement. Spurgeon wrote of Dale: “Among modern divines, few rank as highly as Mr. Dale. Daring and bold in thought, and yet for the most part warmly on the side of orthodoxy, his works command the appreciation of cultured minds.” Thus Dale comes with Spurgeon’s commendation. Dale was a great preacher, and his book Nine Lectures on Preaching (Hodder and Stoughton, 1878) is worth its weight in gold. Dale’s prose style is excellent, and the lessons of this book are lessons that the 21st century needs as much as the 19th. If I had my way, every theological student would have to read this book. If it were widely read, it would vastly improve modern preaching. I intend to give a few select portions from this valuable work to encourage its reading. Dale was an Arminian, but that ought not to keep the Reformed theologian from reading him.

Our first quotation is a rather humorous story with a serious point.

“When you take a text be sure that it is in the Bible. A friends of mine now dead – a very eminent preacher – once made what has been described to me as a very fine sermon on some words which he imagined were in the Book of Proverbs. On Sunday morning, before starting for Church, he thought that it would be as well if he looked up the chapter in which he supposed the words occurred. To his dismay the words were not to be found. He turned to his ‘Cruden,’ but Cruden failed him. He was still confident that the words were in the Book of Proverbs, and when the critical moment came for beginning to preach, he began by saying something to this effect: ‘You will remember, my friends, the words of the wisest of kings’ – then he quoted his text and glided into his sermon as if he had innocently forgotten to say where the words of the wisest of kings occurred. Many a child in the congregation that afternoon hunted in vain through the Book of Proverbs and the Book of Ecclesiastes to discover the text of the morning. I think my friend would have done better if he had warned the people that though he thought the words were Solomon’s, he had not been able to find them, even with the help of a concordance. He discovered afterwards, I think, that the words were in one of the collects or prayers of the Anglican Prayer-book.” – P. 125

“When you take a text be sure that it is in the Bible. A friends of mine now dead – a very eminent preacher – once made what has been described to me as a very fine sermon on some words which he imagined were in the Book of Proverbs. On Sunday morning, before starting for Church, he thought that it would be as well if he looked up the chapter in which he supposed the words occurred. To his dismay the words were not to be found. He turned to his ‘Cruden,’ but Cruden failed him. He was still confident that the words were in the Book of Proverbs, and when the critical moment came for beginning to preach, he began by saying something to this effect: ‘You will remember, my friends, the words of the wisest of kings’ – then he quoted his text and glided into his sermon as if he had innocently forgotten to say where the words of the wisest of kings occurred. Many a child in the congregation that afternoon hunted in vain through the Book of Proverbs and the Book of Ecclesiastes to discover the text of the morning. I think my friend would have done better if he had warned the people that though he thought the words were Solomon’s, he had not been able to find them, even with the help of a concordance. He discovered afterwards, I think, that the words were in one of the collects or prayers of the Anglican Prayer-book.” – P. 125

No comments:

Post a Comment